Please note that all orders to the United States are shipped by economy post without a tracking number. If you would like your order to be sent by priority post with a tracking number, please contact us and we will charge you the priority postage costs.

NEW

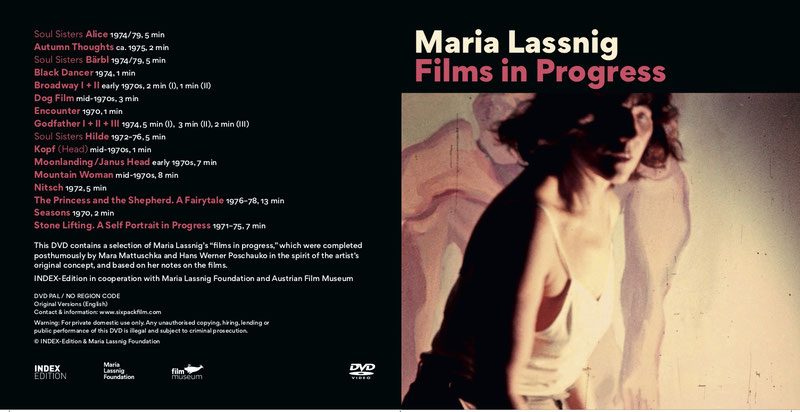

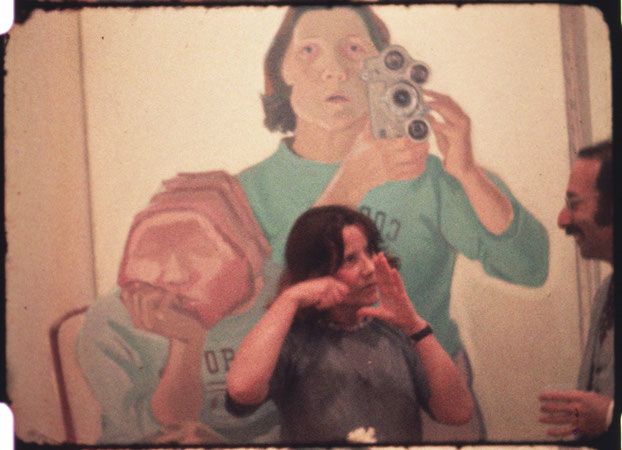

Maria Lassnig (1919–2014) is internationally recognized as one of the most important painters of the 20th and 21st centuries. The leitmotif of her painting, the act of rendering her body awareness visible, found additional expression in film in New York in the early 1970s. While several of these films have long since been part of her canonical works (e.g. Selfportrait, Iris, and Couples), many remained unfinished. These "films in progress" can be regarded as autobiographical notes as well as an artistic experiment featuring many of Lassnig's recognizable subjects and methods. In 2018, this filmic legacy was restored and in many cases completed according to her original concept and instructions by two close collaborators, artists Mara Mattuschka and Hans Werner Poschauko.

This publication, available in English and in German, provides the first comprehensive index of Lassnig's film works, offering insight into the filmmaker's world of ideas through a wide selection of her own, previously unpublished notes. It includes contributions by James Boaden, Beatrice von Bormann, Jocelyn Miller, Stefanie Proksch-Weilguni, and Isabella Reicher and extensive conversations on the rediscovery of Lassnig’s fascinating films.

The enclosed DVD contains a selection of the "films in progress."

Soul Sisters: Watching Maria Lassnig’s Self-Suppressed Films

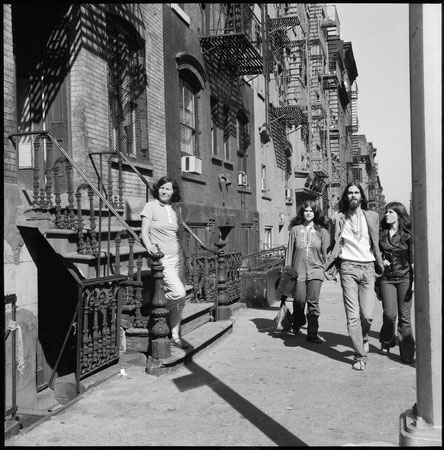

The release of these works reveals a whole other side to the introspective painter, who filmed extensively in 1970s New YorkBest known as a painter, and especially for her innovative self-portraits, Austrian artist Maria Lassnig spent the 1970s in New York. During that time, she worked extensively in moving image, completing several works, including the animated Selfportrait (1971) and Couples (1972), and joining the Women/Artist/Filmmakers, Inc collective with Carolee Schneemann and others. She left New York in 1980, when she received an invitation to teach at the University of Applied Arts, Vienna – which, to her astonishment, met her demand that she be paid the same as her new colleague, Joseph Beuys; she was a chair at the school until 1997, and kept painting for the rest of her life.

After Lassnig died, in 2014, aged ninety-four, two former students, filmmakers Mara Mattuschka and Hans Werner Poschauko, revisited some of the unfinished 8mm and 16mm short films that had sat in a trunk since her return from New York, and that she had not wanted screened again during her lifetime but was willing to let others complete after her death. Finished using Lassnig’s notes and Mattuschka and Poschauko’s intuitions, final cuts and colour corrections, 19 of these works have been released on DVD as Film Works by the Austrian Film Museum. They come with a book that includes reminiscences from Schneemann, Paul McCarthy, Ulrike Ottinger and others, an interview with Mattuschka and Poschauko about the restorations, an article on Lassnig’s sadly unrealised Anti-War Film, in which she planned to address violence and conflict from the ancient era to the present, Lassnig’s essay ‘Animation as a Form of Art’ (1973), scans and transcriptions of her notes and drawings, and an extensive filmography that includes these newly available works.

Poschauko tells us that once Lassnig returned to Vienna, she broke off all contacts in New York. She also distanced herself from the feminist movement that had so interested her there, not wanting to be ‘pigeonholed’ as a woman and using the male form of artist (Künstler, rather than Künstlerin) to describe herself in German. The members of Women/Artist/Filmmakers, Inc shared few stylistic or political principles, making these works hard to place within that context, but Schneemann remembered them fondly, calling them ‘charming, ironic, shifting between static images and density in motion… always colourful with a subtle, brutal gender appetite towards erotic happiness’. Indeed, the Film Works are more outward-looking than her intimate, introspective self-portraits and animations – perhaps because, as Lassnig is quoted here as saying, in film, the ‘eyes of the painter are half-replaced by a machine that makes its own demands’.

Several of them are from Lassnig’s Soul Sisters series, made between 1972 and 1979, where she created portraits of her friends Alice, Bärbl and Hilde. As with the rest of the collection, they are prefaced with an explanation of their format, length, whether they were a rough or final cut, and what is used to soundtrack them – in these instances, works by Anton Webern and George Frideric Handel. Lassnig uses English-language voiceovers for Alice and Bärbl, speaking in sympathy with two women struggling in their relationships: Alice, an Icelandic artist who moved to New York, couldn’t keep up with her many boyfriends and disappeared “like a comet”; “typical Austrian woman” Bärbl was frustrated with a partner she rarely saw, and felt she might rather be alone. In their detached view of sexuality and creative use of the naked body – Alice, blindfolded, pins the names of her lovers and their defining qualities to the wall, and then to herself – these films recall Lassnig’s younger compatriot VALIE EXPORT. But there is no distancing of the viewer from the subject through experimentation with 16mm form, as with many works by the London Film-Makers’ Co-operative, or structural filmmakers such as Kurt Kren. Besides EXPORT, whose films are generally far more confrontational, it’s hard to discern many influences on Lassnig, but easier to see how her approach inspired Austrian artists such as Mattuschka, Ursula Pürrer and Ashley Hans Scheirl, whose portraits of themselves and their friends during the 1980s share a similar playfulness.

Autumn Thoughts (c. 1975) is, like Black Dancer (1974), concerned with movement as a way of conveying personality, displaying the influence of Maya Deren – often cited as the founder of US avant-garde film, and one of the only women included in histories of its development before the 1970s. In just two minutes, Autumn Thoughts efficiently contrasts a melancholic, middle-aged woman (Lassnig) gazing into water with a youthful male dancer, quickening the film’s tempo and blurring its frames to emphasise the divides between young and old, suggesting in the cutting between the two figures that while men see (heterosexual) relationships as a source of energy, for women they can be exhausting.

Other films engage with the media in wryly amusing ways. Francis Ford Coppola shot parts of The Godfather: Part II (1974) near Lassnig’s studio, so she joined them on set, capturing the 1920s ‘Little Italy’ that Coppola had recreated in the East Village, calling her piece Godfather I, II and III. Her use of double exposure gives the sense of two time periods happening simultaneously, while a lens that shifts in and out of focus reminds viewers that they’re watching a film – but it’s only when Lassnig catches an important moment in Coppola’s narrative that we realise we’re watching a ‘drama’.

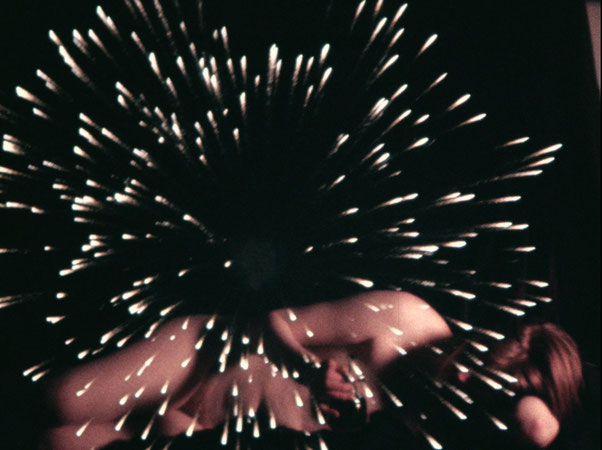

Moonlanding/Janus Head (1971–72) combines found footage of a NASA mission (it’s not clear which), figure skating and American football with Lassnig’s own material. Again, she uses multiple exposures for dramatic effect, suggesting this bombardment of images and stimuli can be invigorating rather than overwhelming, and capitalising on the shared sense of wonder at the televised broadcasts from the Moon.

The centrepiece, and longest film of the collection, also shown as a work in progress during Lassnig’s lifetime and then left unfinished, is The Princess and the Shepherd. A Fairytale (1976–78). Lassnig examines the gendered tropes and clichés of the genre without overbearing cynicism, mocking its male archetypes with the subtle brutality that Schneemann highlighted in her recollections. Its conclusion, with the princess opting for a simple life over social expectations, is perhaps unsurprising from an artist who always valued honest self-expression and personal independence above all else.

Juliet Jacques, 09 April 2021, ArtReview

Maria Lassnig, die Soul Sister mit Schmäh

Das Buch "Maria Lassnig. Das filmische Werk" beschäftigt sich mit den lange unterbeleuchteten Filmen der Künstlerin. Praktischerweise gleich inklusive DVD

Eine der bedeutendsten österreichischen Künstlerinnen hielt für die Nachwelt einen Schatz bereit. In ihrer Wohnung verwahrte Maria Lassnig in einer Kiste Filme, die sie in den 1970er-Jahren in New York verwirklicht hatte, bevor sie sich nach ihrer Rückkehr nach Wien hauptsächlich wieder der Malerei zugewandt hat.

Ein Geschenk, zunächst vor allem aber eine heikle Aufgabe für Kenner und Restaurateure ihres Werks. Mara Mattuschka und Hans Werner Poschauko fiel die Aufgabe zu, das lose Material – Super-8- und 16mm-Formate, einzelne Filmkader wurden teils nur mit Malerkreppband zusammengehalten – in mühevoller Arbeit zu bergen und zu rekontextualisieren.

Der Schatz, Lassnigs nunmehr titulierte "Films in Progress", wurde im New Yorker MoMA und anschließend im Österreichischen Filmmuseum präsentiert, jetzt sind die Filme auch dem neu erschienenen Buch Maria Lassnig. Das filmische Werk als DVD beigelegt. Kannte man Lassnig im filmischen Bereich als Verfechterin eines höchst eigensinnigen Animationsfilms – das Wort "Trickfilm" behagte ihr nie richtig –, mit dem sie ihre Körperstudien zu beweglichen Metamorphosen beschleunigte, so liefern diese Arbeiten das Bild einer in vielerlei Richtungen experimentierfreudigen Filmkünstlerin.

In Godfather I, II, III bewegt sie sich etwa 1974 wie ein Zaungast durch die Sets von Francis Ford Coppolas Dreh von Der Pate 2. Selbst wenn der Regisseur darin in einem bunten Wintermantel kurz wie ein narzisstischer Harlekin auftaucht, begeistert sich Lassnigs in Mehrfachbelichtungen gedrehter Film mehr für die Verwandlung von Little Italy, wo Gegenwart und filmmythologische Inszenierung zu einem Bild verwachsen.

Weiblicher Dionysos

Solche Verdichtung wird in Moonlanding/Janus Head noch radikal gesteigert. Da lässt Lassnig TV-Bilder von der US-Mondlandung, Kriegs- und Spielfilmszenen mit Eisläuferinnen, tanzenden Beinen und einer dionysischen, an Weintrauben kauenden Frauenfigur in Dialog treten – am Ende wird das Filmbild zerkratzt, als wären die Kufen darübergerast.

Lassnig ging auch deshalb nach New York, um ihre Position als Frau in der Kunst schärfen zu können. James Boaden rekonstruiert in einem der Essays des Buches den kulturgeschichtlichen Horizont der Szene, in die die Österreicherin eintrat, um ihr "Körperbewusstsein" an gegenwärtigen Verhältnissen zu messen. Der Film war das Medium der Zeit – wobei Lassnig, wie sie in einem schönen Text schreibt, improvisieren musste: ihr "Animationspult, das sind zwei Plastikbücher, auf ein Stanniolpapier gelegt; zwischen ihnen befindet sich eine längliche Glühbirne, darüber als Brücke eine Milchglasplatte".

Doch auf sich allein gestellt war sie nicht, denn es lag der Geist der Kollektivierung in der Luft. Lassnig gehörte neben Carolee Schneemann, Rosalind Schneider oder Yvonne Rainer zur feministischen Gruppe Women Artist Filmmakers, Inc., mit der man gegen die Marginalisierung von Frauen in einer Kunstszene antrat, die selbst im Underground-Bereich schon wieder patriarchale Strukturen herausbildete – rund um das Anthology Film Archive wurde eifrig an einem "Kanon des Films" gebastelt.

Lassnigs Soul Sisters-Serie, ihre so witzigen wie feinfühligen Porträts befreundeter Frauen, kann man dahingehend als Ergänzung verstehen. In Alice rückt sie etwa einer Isländerin nahe, die in New York wie ein "funkelnder Komet" eingeschlagen war. Nackt besprüht sich diese mit Wein, anschließend werden ihre vielen "boyfriends" rückblickend mit Eigenschaften versehen und als Kärtchen am Körper befestigt – denn "gut waren sie schließlich alle".

Das Buch enthält übrigens auch zahlreiche Faksimile, die Einblick in Lassnigs unrealisierte Ideen gestatten. Eine davon lautet: "Ich möchte einen Mann, den ich auf u. abdrehn kann wie TV."

Dominik Kamalzadeh, 13.2.2021, derstandard.at

Please note that all orders to the United States are shipped by economy post without a tracking number. If you would like your order to be sent by priority post with a tracking number, please contact us and we will charge you the priority postage costs.