Tito-Material

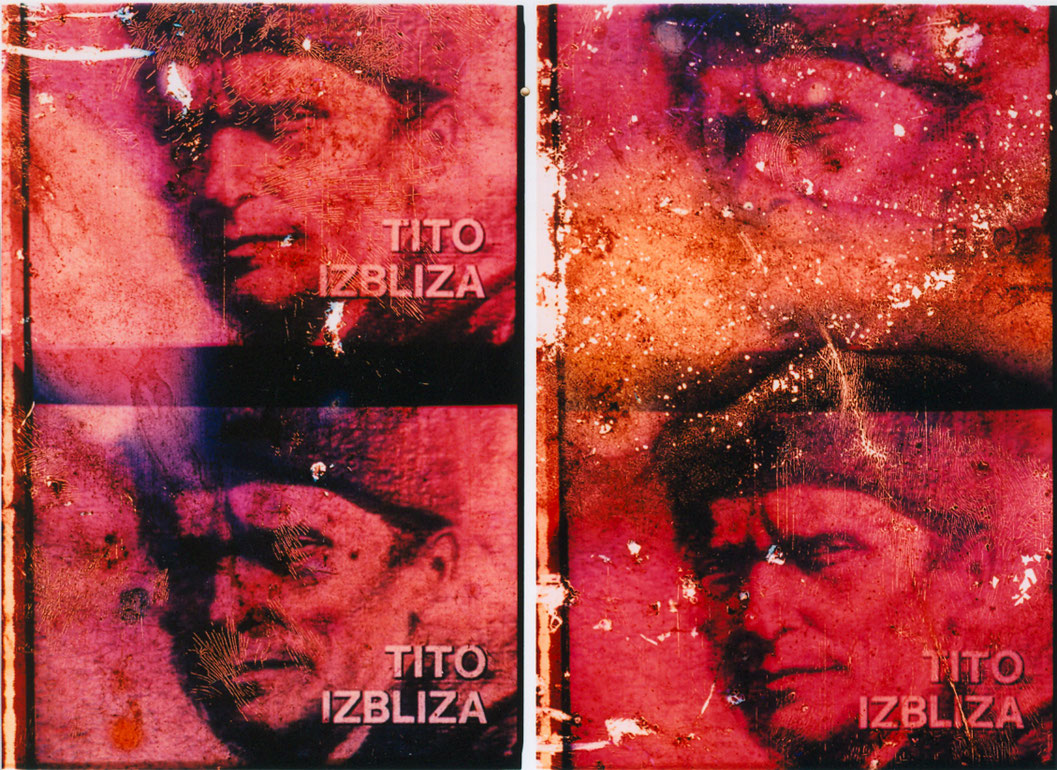

Found material: film images which show Tito in diverse contexts, at public affairs, with the Partisans, in "private" while shaving, etc. Place of discovery: a destroyed cinema in Mostar, Bosnia in 1996. The film construction, created at the optical printer, is of course also a counter concept to the more narrative models: the marks of war are not primarily made visible on the representational level, but more through the damage done to the film material itself from rubble and dampness, but also through the film´s editing.

(Birgit Flos)

More Texts

Thomas Korschil about Tito-Material

Elke Groen salvaged fragments of a film from the rubble of a cinema in war-torn Mostar. It was called

Tito from close up and dated from around 1978. The weathered film, riddled with traces of time and history

shows Tito at public events, together with partisans and "in private". The material is in the process of

decay. Holes gapes through the emulsion. Some passages have become completely abstract and only consist

of shapes and colours. Groen investigated this strip of film, felt its scuffs, tears and folds and

photographed the fluctuating colours as well as the accumulated dirt. She doesn't force the fragment

into a unified structure, but instead tries various things out as she goes along. She notes details,

enlarges parts of the images (and thus, also, the grain). She lays down short loops, makes the pictures

flicker, has them hesitate or even come to a stand still. She reacts to the origins and historical

context of the piece cautiously. She notes things and comments events that can only be touched on

indirectly in this film. The context is inherently emotionally charges, the beauty of the dissolving

pictures sometimes over-powering. The original source was apparently a propaganda film of a system now

consigned to the history books, and it made extensive use of pictures from the Second World War. Groen's

selection of material uses these images very sparingly. Her film hints at things, no more and no less.

Thomas Korschil

Tito from close up and dated from around 1978. The weathered film, riddled with traces of time and history

shows Tito at public events, together with partisans and "in private". The material is in the process of

decay. Holes gapes through the emulsion. Some passages have become completely abstract and only consist

of shapes and colours. Groen investigated this strip of film, felt its scuffs, tears and folds and

photographed the fluctuating colours as well as the accumulated dirt. She doesn't force the fragment

into a unified structure, but instead tries various things out as she goes along. She notes details,

enlarges parts of the images (and thus, also, the grain). She lays down short loops, makes the pictures

flicker, has them hesitate or even come to a stand still. She reacts to the origins and historical

context of the piece cautiously. She notes things and comments events that can only be touched on

indirectly in this film. The context is inherently emotionally charges, the beauty of the dissolving

pictures sometimes over-powering. The original source was apparently a propaganda film of a system now

consigned to the history books, and it made extensive use of pictures from the Second World War. Groen's

selection of material uses these images very sparingly. Her film hints at things, no more and no less.

Thomas Korschil

Thomas Korschil zu Tito-Material dt

Aus dem Schutt eines im Krieg zerstörten Kinos in Mostar barg Elke Groen Fragmente eines mit Tito

hautnah überschriebenen Films (zirca 1978). Die verwitterten, mit Spuren von Zeit und Geschichte

übersäten Stückchen zeigen Tito bei öffentlichen Auftritten, bei den Partisanen und "privat". Das

Material befindet sich in Auflösung. Löcher klaffen in der Emulsion. Manche Passagen sind völlig

abstrakt geworden, sind nur mehr Farbe und Form. Diese Streifen untersucht Groen, tastet ihre Schrammen,

Risse und Falten ab, fotografiert

die fluktuierenden Farben und auch den akkumulierten Schmutz. Dabei zwingt sie die Fragmente nicht

in eine durchgängige Struktur, sondern probiert verschiedenes aus in ihrer übertragung. Sie geht

ins Detail, vergrößert Bildausschnitte und damit auch das Korn. Sie legt kurze Schleifen, bringt

Bilder ins Flackern und ebenso ins Stocken oder zum Stillstand. Mit Herkunft und geschichtlichem

Kontext des Materials versucht Groen behutsam umzugehen. Sie macht Notizen, Anmerkungen zu

Ereignissen, die in diesem Film nur indirekt zur Sprache kommen können. Die Bezüge sind von

vornherein aufgeladen, die Schönheit der sich auflösenden Bilder manchmal überwältigend. Die

ursprüngliche Quelle war ein offenbar propagandistischer Film eines mittlerweile untergegangen

Systems, der sich in seiner Erzählung massiv an Bildern des Zweiten Weltkrieges bedient hat.

Groen verwendet diese in ihrer Auswahl nur sehr sparsam. Ihr Film will andeuten, nicht mehr und

nicht weniger.

Thomas Korschil

hautnah überschriebenen Films (zirca 1978). Die verwitterten, mit Spuren von Zeit und Geschichte

übersäten Stückchen zeigen Tito bei öffentlichen Auftritten, bei den Partisanen und "privat". Das

Material befindet sich in Auflösung. Löcher klaffen in der Emulsion. Manche Passagen sind völlig

abstrakt geworden, sind nur mehr Farbe und Form. Diese Streifen untersucht Groen, tastet ihre Schrammen,

Risse und Falten ab, fotografiert

die fluktuierenden Farben und auch den akkumulierten Schmutz. Dabei zwingt sie die Fragmente nicht

in eine durchgängige Struktur, sondern probiert verschiedenes aus in ihrer übertragung. Sie geht

ins Detail, vergrößert Bildausschnitte und damit auch das Korn. Sie legt kurze Schleifen, bringt

Bilder ins Flackern und ebenso ins Stocken oder zum Stillstand. Mit Herkunft und geschichtlichem

Kontext des Materials versucht Groen behutsam umzugehen. Sie macht Notizen, Anmerkungen zu

Ereignissen, die in diesem Film nur indirekt zur Sprache kommen können. Die Bezüge sind von

vornherein aufgeladen, die Schönheit der sich auflösenden Bilder manchmal überwältigend. Die

ursprüngliche Quelle war ein offenbar propagandistischer Film eines mittlerweile untergegangen

Systems, der sich in seiner Erzählung massiv an Bildern des Zweiten Weltkrieges bedient hat.

Groen verwendet diese in ihrer Auswahl nur sehr sparsam. Ihr Film will andeuten, nicht mehr und

nicht weniger.

Thomas Korschil

Seven Instances of the Austrian Avant-Garde, by Ed Halter

Thomas Bernhard tells the story of two professors at the University of Graz who move themselves and their families into a single house together for the purpose of continuing an entrenched, decades-long philosophical argument. After embroiling a third colleague in the dispute, they invite him over to their shared home, then blow up the buildingthus ending the discussion. They had spent all the money they had left, Bernhard writes, on the dynamite necessary for the purpose.

Imagine this tale as a parable of the distinctive paradoxes of avant-garde cinema. Exceedingly erudite conceptual structures and complex aesthetic systems achieve realization through collisions of light and sound, designed to throw the viewer into a confrontation with the barest elements of cinematic form, made possible with the slightly antiquated products of 19th century science. The formalist edge of Austrian filmmaking has always pushed such extremesmachine flatness and spiritual emotion, animal shock and cognitive puzzle, fleshy materialism and ghostly mystery.

Austrias success in fostering such a powerful experimental film scene is well known among cineastes worldwide. A conflux of generative factors can be cited: the storied history of avant-garde art and literature in Vienna; the influence of filmmakers such as Valie Export, Peter Kubelka and Kurt Kren, who attained international renown decades ago; the success of shorts distributor sixpackfilm, which has helped keep Austrian artists prominent in international festivals; and, not least, the long-standing commitment of governmental organizations such as Film Division of the Department of the Arts to fund such adventurous, non-narrative films. Dynamite doesnt come cheaply.

Look at a sample seven titles underwritten by the Film Division, and the impact of this sustained support will be made clear.

1. Kurt Kren, 49/95 Tausendjahrekino (1995)

There is a discernable sensibility to Austrian experimentsa cluster of threads that run through many of finest examples of filmmaking. Commissioned to mark the cinemas centenary, Krens Tausendjahrekinoopens with a title screen speckled with black bits of dust and detritus, then volleys through staccato flashes of tourists pointing cameras up at the St Stephens Cathedral in Vienna. Each of their banal snaps is countered by Krens guerrilla anthropology, captured with his shaking, zooming lens. Like this one, the best Austrian films are short, brutal and dirty.

2. Martin Arnold, Alone. Life Wastes Andy Hardy (1998)

Arnold takes Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney, two icons of innocent 1930s Americana, then stretches and remixes their language and body movements into a minuet of robotic jitters and beastly bleats, uncovering an uneasy sexual tension in the triangle of girl, boy and mother. The filmmaker digs deeps, hits nerves.

3. Elke Groen, Tito-Material (1998)

From the rubble of a decimated cinema in Bosnia and Herzogovina, Groen found propaganda newsreel footage of Yugoslavian President-for-Life Tito. Reprinted, Tito moves silently under layers of decay. Peter Gidal once defined materialist cinema as trafficking in that space of tension between materialist flatness, grain, light, movement, and the supposed reality that is represented. To this Tito-Materialadds the tension between past and present, state-sponsored fantasy and political reality.

4. Gustav Deutsch, Film Ist. (1998/2002)

The past becomes an ever stranger land in Film Ist. , filled with disjunctive colonialist mansions, supernatural religious footage, and accidentally surrealist science documentaries, all snatched from the era of silent cinema. These fragments are slowed down, re-cut and set to staticky electronic soundscapes. The flicker and hum evoke a hypnotic state: revisiting times lost as a form of disembodied dreaming. The soundtrack itself presages the experiments in digital, visual glitch seen in a more recent generation of Austrian video art.

5. Siegfried A. Fruhauf, Exposed (2001)

White oblong shapes float like clouds across one another, sailing across an expanse of movie-screen blackness, each glowing box in the round-cornered shape of a 16mm sprocket hole. One again a spirit is summoned from the very materials of the machine.

5. Kerstin Cmelka, Camera (2002)

In Cmelkas earlier films, Mit Mir and Et In Arcadia Ego, the filmmaker plays with her own doppelgangers, superimposing herself upon herself multiple times. Camera uses similar optical tricks to print moving images of woodlands on the interior walls of a small room. Recall that camera merely means room or chamber in Latin: so is the film camera offer a window on the world, or merely in illusion of one? Maybe we cant really leave the roomor cameraafter all.

7. Peter Tscherkassky, Instructions for a Light and Sound Machine (2005)

American critics blithely assume that films from outside our borders always comment on our own cultureas if the worlds artistic output had the mere function of an elaborate vanity mirror for us (So, tell me honestly, how do I look?). But here such a claim does not feel like this kind of indulgence. Tscherkassky takes moments from The Good, The Bad and the Ugly and handprints them into a rat-a-tat-tat wartime montage. The throb of exploding bullets reminds us of the clacking of the projector over our heads: the reflection throws us out of the theater and back into the world.

* * *

Certainly not every nation that has chosen to invest its capital into filmmaking has been as fortunate as Austria with the cultural returns. In many other nations, governmental financing and grant foundations make the mistake underwriting the bland and inoffensive. The strategy in Austria seems to have been to support the strongest elements of the idiosyncratic and rebellious fringe, to encourage daringly noncommercial work, and to strive for art, rather than mere entertainment.

Look at key words from these seven titles: kino, waste, material, film, exposed, camera, light and sound machine. Austrian experimental cinema always returns to contemplate its own being, but in doing so, seeks new engagement with the world.

Imagine this tale as a parable of the distinctive paradoxes of avant-garde cinema. Exceedingly erudite conceptual structures and complex aesthetic systems achieve realization through collisions of light and sound, designed to throw the viewer into a confrontation with the barest elements of cinematic form, made possible with the slightly antiquated products of 19th century science. The formalist edge of Austrian filmmaking has always pushed such extremesmachine flatness and spiritual emotion, animal shock and cognitive puzzle, fleshy materialism and ghostly mystery.

Austrias success in fostering such a powerful experimental film scene is well known among cineastes worldwide. A conflux of generative factors can be cited: the storied history of avant-garde art and literature in Vienna; the influence of filmmakers such as Valie Export, Peter Kubelka and Kurt Kren, who attained international renown decades ago; the success of shorts distributor sixpackfilm, which has helped keep Austrian artists prominent in international festivals; and, not least, the long-standing commitment of governmental organizations such as Film Division of the Department of the Arts to fund such adventurous, non-narrative films. Dynamite doesnt come cheaply.

Look at a sample seven titles underwritten by the Film Division, and the impact of this sustained support will be made clear.

1. Kurt Kren, 49/95 Tausendjahrekino (1995)

There is a discernable sensibility to Austrian experimentsa cluster of threads that run through many of finest examples of filmmaking. Commissioned to mark the cinemas centenary, Krens Tausendjahrekinoopens with a title screen speckled with black bits of dust and detritus, then volleys through staccato flashes of tourists pointing cameras up at the St Stephens Cathedral in Vienna. Each of their banal snaps is countered by Krens guerrilla anthropology, captured with his shaking, zooming lens. Like this one, the best Austrian films are short, brutal and dirty.

2. Martin Arnold, Alone. Life Wastes Andy Hardy (1998)

Arnold takes Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney, two icons of innocent 1930s Americana, then stretches and remixes their language and body movements into a minuet of robotic jitters and beastly bleats, uncovering an uneasy sexual tension in the triangle of girl, boy and mother. The filmmaker digs deeps, hits nerves.

3. Elke Groen, Tito-Material (1998)

From the rubble of a decimated cinema in Bosnia and Herzogovina, Groen found propaganda newsreel footage of Yugoslavian President-for-Life Tito. Reprinted, Tito moves silently under layers of decay. Peter Gidal once defined materialist cinema as trafficking in that space of tension between materialist flatness, grain, light, movement, and the supposed reality that is represented. To this Tito-Materialadds the tension between past and present, state-sponsored fantasy and political reality.

4. Gustav Deutsch, Film Ist. (1998/2002)

The past becomes an ever stranger land in Film Ist. , filled with disjunctive colonialist mansions, supernatural religious footage, and accidentally surrealist science documentaries, all snatched from the era of silent cinema. These fragments are slowed down, re-cut and set to staticky electronic soundscapes. The flicker and hum evoke a hypnotic state: revisiting times lost as a form of disembodied dreaming. The soundtrack itself presages the experiments in digital, visual glitch seen in a more recent generation of Austrian video art.

5. Siegfried A. Fruhauf, Exposed (2001)

White oblong shapes float like clouds across one another, sailing across an expanse of movie-screen blackness, each glowing box in the round-cornered shape of a 16mm sprocket hole. One again a spirit is summoned from the very materials of the machine.

5. Kerstin Cmelka, Camera (2002)

In Cmelkas earlier films, Mit Mir and Et In Arcadia Ego, the filmmaker plays with her own doppelgangers, superimposing herself upon herself multiple times. Camera uses similar optical tricks to print moving images of woodlands on the interior walls of a small room. Recall that camera merely means room or chamber in Latin: so is the film camera offer a window on the world, or merely in illusion of one? Maybe we cant really leave the roomor cameraafter all.

7. Peter Tscherkassky, Instructions for a Light and Sound Machine (2005)

American critics blithely assume that films from outside our borders always comment on our own cultureas if the worlds artistic output had the mere function of an elaborate vanity mirror for us (So, tell me honestly, how do I look?). But here such a claim does not feel like this kind of indulgence. Tscherkassky takes moments from The Good, The Bad and the Ugly and handprints them into a rat-a-tat-tat wartime montage. The throb of exploding bullets reminds us of the clacking of the projector over our heads: the reflection throws us out of the theater and back into the world.

* * *

Certainly not every nation that has chosen to invest its capital into filmmaking has been as fortunate as Austria with the cultural returns. In many other nations, governmental financing and grant foundations make the mistake underwriting the bland and inoffensive. The strategy in Austria seems to have been to support the strongest elements of the idiosyncratic and rebellious fringe, to encourage daringly noncommercial work, and to strive for art, rather than mere entertainment.

Look at key words from these seven titles: kino, waste, material, film, exposed, camera, light and sound machine. Austrian experimental cinema always returns to contemplate its own being, but in doing so, seeks new engagement with the world.

Orig. Title

Tito-Material

Tito-Material

Year

1998

1998

Country

Austria

Austria

Duration

5 min

5 min