Cinema Futures

The “digital revolution” reached the cinema late and was chiefly styled as a technological advancement. Today, in an era where analog celluloid strips are disappearing, and given the diversity of digital moving picture formats, there is much more at stake: Are the world´s film archives on the brink of a dark age? Are we facing the massive loss of collective audiovisual memory? Is film dying, or just changing?

Cinema Futures travels to international locations and, together with renowned filmmakers, museum curators, historians and engineers, dramatizes the future of film and the cinema in the age of digital moving pictures.

________________

Cinema Futures is a documentary film about the present and future of film and the cinema in the digital era. In individual episodes and cinematic aphorisms, future scenarios, cultural fears and promising utopias are sketched out, accompanying the epochal transition from an approximately 120-year history of analog photochemical celluloid strips to the immaterial and radically evanescent age of digital picture data streams. The focus is on a love of the cinema, albeit devoid of nostalgia.

What is at stake is the specific cultural technique and experience of analog film, the preservation of audiovisual heritage in film and television archives, the storing, restoration and conservation of moving pictures on film and magnetic tapes, and the promises of salvation made by the pseudo-eternity of bits and bytes. Cinema Futures oscillates between a technocratic belief in progress and apocalyptic visions of the total erasure of our audiovisual memory: On one hand, there is the concept of the digital as a way to overcome the ephemeral - in other words ensuring democratic access to our audiovisual heritage. On the other hand, the vision of our present as a future “dark age” looms, of which not much will be preserved, as film as a physical object and cinema as a techno-social infrastructure become obsolete and digital data becomes unreadable. What will become of the images and memories of our times and of days gone by when they no longer have an analog, physical presence? In light of the acute mutations in the way film is produced and received overall, nobody can precisely predict what the future will hold. Filmmakers, film and television archives are just now tackling this debate. And archival collections are just beginning to be digitized and stored on gigantic server systems. How long will the data remain readable and accessible in this digital Noah´s Ark? What do we gain, and what do we lose?

Cinema Futures is an associative journey through time, filmed at international locations, where we meet up with renowned filmmakers, museum curators, historians and engineers.

With Martin Scorsese, Christopher Nolan, Tacita Dean, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, David Bordwell, Tom Gunning, Jacques Rancière, Margaret Bodde, Paolo Cherchi Usai, Nicole Brenez, Michael Friend, Greg Lukow, Mike Mashon, and many others.

Alles wird digital, von Thomas Mießgang, Die Zeit, 24.10.2016 (Article)

Es ist ein Desaster: Wenn sich die Faust um den Zelluloidstreifen schließt, zerbröselt der Film wie Zwieback. Manchmal ist das Material in der Aluminiumdose aber auch so hart, dass man die Rolle gar nicht mehr abspulen kann. "Wir sagen Eishockey-Puck dazu", erläutert George Willeman, Filmrestaurator der amerikanischen Library of Congress. Ein Film, der sich aufgrund von Alter oder unsachgemäßer Lagerung zersetzt, ist aber auch eine olfaktorische Belästigung: "Diese Filme beginnen nach Essig zu riechen. Der Geruch ätzt einem die Haare in den Nasenlöchern weg. Wenn man jetzt nicht handelt, ist ein Werk für immer verloren." Noch einmal greift der Restaurator zu der Filmdose und kippt sie so, dass die Brösel zu tanzen beginnen: "Schade, das war das Originalnegativ von George Meliés´ Der wandernde Jude." Er führe einen Kampf gegen die Zeit, sagt Willeman, den er eigentlich nicht gewinnen könne. Denn 75 Prozent des Materials aus der Stummfilmzeit sei bereits unwiederbringlich verloren.

Der Mitarbeiter der größten amerikanischen Institution zur Bewahrung und Sicherung von moving images ist einer von Dutzenden Archivaren, Kuratoren, Kritikern und Regisseuren, die in Cinema Futures, einem Film des österreichischen Regisseurs Michael Palm, über Gegenwart und die prekäre Zukunft des Kinos reflektieren und spekulieren. Nach den Filmfestspielen von Venedig ist die Dokumentation nun auch bei der Viennale zu sehen.

Es geht um die digitale Revolution, die in den letzten Jahren stattgefunden hat, und um die Konsequenzen, die diese fundamentale Umwälzung für den traditionellen Film hat, der nach 120 Jahren glorreicher Kinogeschichte zum Minderheitenprogramm geworden ist. Es geht aber auch um die Frage, was mit den Bildern und Erinnerungen an unsere und vergangene Zeiten in den kommenden Jahren und Jahrzehnten passieren wird.

DIE ZEIT 44/2016

Dieser Artikel stammt aus der Österreich-Ausgabe der ZEIT Nr. 44 vom 20.10.2016. Sie finden diese Seiten jede Woche auch in der digitalen ZEIT. Die aktuelle ZEIT können Sie am Kiosk oder hier erwerben.

Da gibt es zum einen jene, die mit gewaltigem Einsatz von finanziellen Mitteln und Arbeitskraft versuchen, das audiovisuelle Gedächtnis der Menschheit in Form des analogen fotochemischen Filmstreifens für die Archive und die Filmmuseen zu bewahren. Und dann die anderen, die sich längst damit abgefunden haben, dass die Zukunft digital sein wird und der traditionelle Film eine aussterbende Gattung ist: ein Museumsstück, das keine Massenbasis mehr hat und in cinephilen Aufführungsorten unter privilegierten Bedingungen für ein fachkundiges Publikum gezeigt wird. "Diese Haltung ist mir eigentlich nicht sympathisch", sagt Michael Palm, "das erinnert an Gastrokritiker-Veranstaltungen und macht die Cinemathek zum visuellen Äquivalent eines Gourmettempels." Der Film sei jedoch immer ein populäres Medium für die Massen gewesen, ohne Weihrauch und Heiligenschein: "Ich bin überhaupt nicht gegen das Digitale, das wäre heuchlerisch. Ich arbeite ja selbst längst mit digitalen Medien. Aber ich vertrete die Meinung, dass die analoge Option weiterhin möglich sein muss."

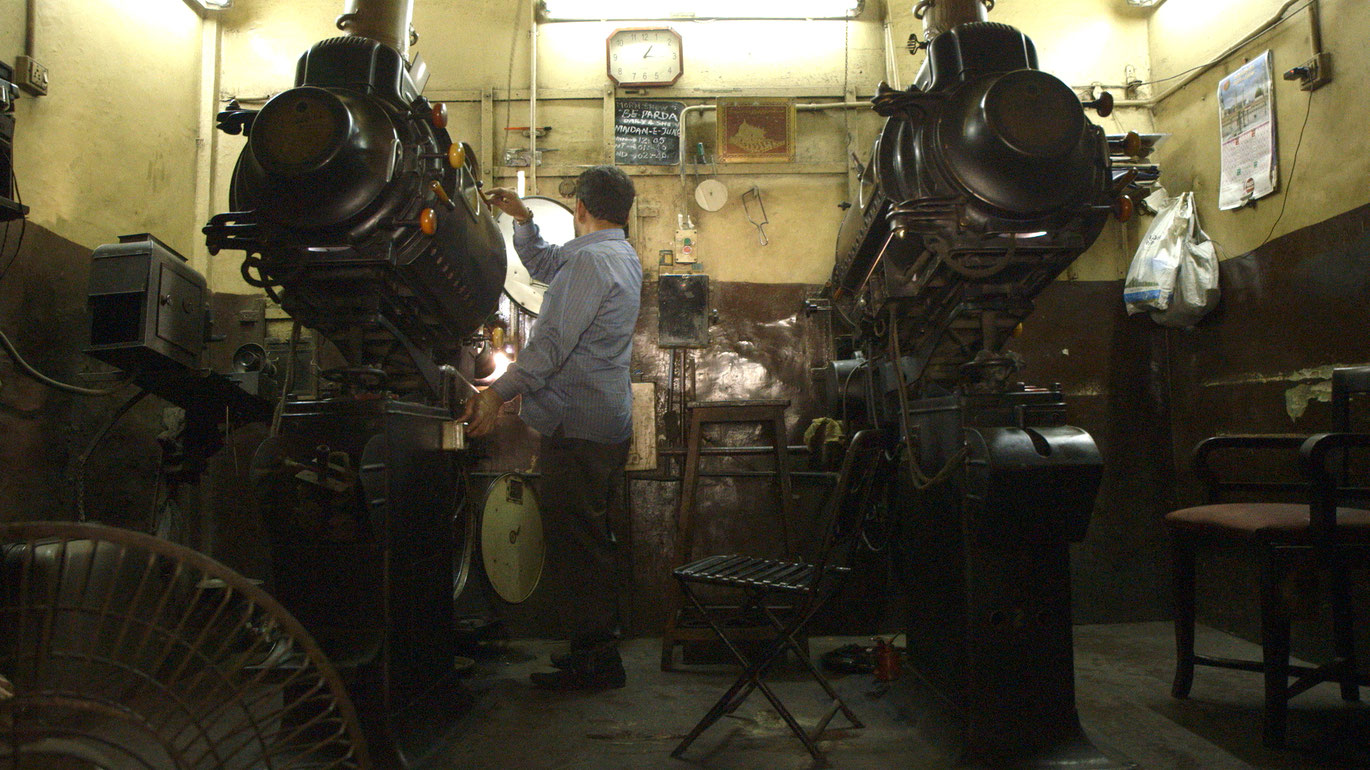

Das Filmgeschäft in den kommerziellen Kinos und Cineplexen findet allerdings längst schon unter volldigitalen Bedingungen statt: Es gibt keine Filmstreifen mehr, die mechanisch bewegt werden, und keine ratternden Projektoren, sondern nur noch einen Server, das sogenannte DCP, Digital Cinema Package, das Bild- und Tondaten in einem speziellen Format enthält und beinahe vollautomatisch auf die Leinwand bringt. Mit dieser neuen Form der Projektion wurde die ganze Inftrastruktur der traditionellen Filmpräsentation obsolet. Statt Filmrollen umzuspulen, startet der Vorführer, dessen Beruf vom Aussterben bedroht ist, nunmehr den Streifen per Mausklick. Trotz des durchschlagenden Erfolges der Digitalisierung im Kino bleibt die Technologie aber mit Problemen behaftet: Sie eignet sich nur begrenzt für die Langzeitsicherung von Filmen, weil digitale Files schneller verloren gehen können als belichtete Zelluloidstreifen. Und sie zwingen zur permanenten Migration der Daten, weil alle paar Jahre neue Trägermedien und Abspielsysteme entwickelt werden. "Das digitale Medium ist ein äußerst unsicheres Gefährt", sagt der experimentelle Filmemacher Peter Kubelka, der in den sechziger Jahren das Wiener Filmmuseum gegründet hat und damit schon per definitionem für den analogen Film als Kunstwerk kämpft.

Die Umstellung des Kinos auf Bits und Bytes, die durch publikumswirksame 3-D-Spektakel zügig vorangetrieben wurde, hat zu einer erbitterten ideologischen Auseinandersetzung zwischen den Befürwortern des analogen Films und den Apologeten einer strahlenden digitalen Zukunft geführt. Anhänger des Zelluloids, zu denen auch berühmte Regisseure wie Christopher Nolan oder Quentin Tarantino zählen, die noch immer auf Film drehen, stört das überhelle, gestochen scharfe Bild ohne Kratzer und Staub, das sich am Heimkino der Flachbildschirme orientiert. Sie bemängeln falsche Farbwerte und Aufnahmen, die in Pixelbrei ausfasern. "Die Fetischisierung des glatten, seine Geschichtlichkeit negierenden Bildes", heißt es auf der Cineasten-Webseite critic.de, "ist schon aus Prinzip abzulehnen." Für Peter Kubelka ist das Digitale schlicht und einfach ein anderes Metier: Die Möglichkeit, Bild und Ton auf Smartphone-Displays, Tablets oder auf Bildschirmen in Bus, Bahn und Flugzeug, also in jeder erdenklichen Lebenssituation, zum Laufen zu bringen. Das Kino, wie er es verstehe, basiere jedoch auf einem Vertrag mit dem Publikum: "Die Leute kaufen eine Eintrittskarte und verweilen dann zwei Stunden in diesem dunklen, akustisch abgeschlossenen Raum. Sie leben im Kopf des Filmautors und geben sich seinem Werk für einen gewissen Zeitraum ganz hin. Im Fall des analogen Films ist diese Situation in unserer Gegenwart mit Abstand die wunderbarste, großartigste Zeit, die sich Leute schaffen können, um mit den Gedanken von jemand anderem zu kommunizieren."

Weniger dogmatische Experten für das bewegte Bild hingegen beharren nicht auf der Black Box eines "unsichtbaren Kinos", wie es Kubelka einst konzipiert hat, als exklusivem Aufführungsort für Filme, sondern plädieren für ein Betrachten auch unter nicht perfekten Bedingungen: Die Pariser Filmwissenschaftlerin Nicole Brenez betonte bei einem Symposion, das 2014 ausgerechnet im Wiener Filmmuseum stattfand, den Nutzen von Filmen im Internet. Man könne sie einfach auschecken, zurate ziehen, benutzen und dabei das geheiligte Ritual der Projektion ausblenden. Es handle sich dann eben um "Konsultations-Versionen". Und der Kunsthistoriker Chris Dercon, Leiter der Tate Modern, pries gar provokant die Vorzüge des Schlafens im Kino und war der Meinung, man solle sperrige Avantgardefilme im Flugzeug zeigen.

Die digitale Projektion braucht allerdings keine Unterstützung durch Cineasten, denn der Kampf der Systeme scheint längst entschieden: Es gibt kaum noch Kinos, die über Projektoren verfügen, die wenigen verbliebenen Kopierwerke sind von der Schließung bedroht, und Kodak ist eine der letzten Firmen, die überhaupt noch Film herstellt. "Der analoge Film wird sterben", sagt Peter Kubelka, "und wird wieder auferstehen – das ist wie in der Natur. Jetzt sind wir in der schwärzesten Phase." Doch schon keimt Hoffnung, denn die großen Hollywood-Studios würden mittlerweile Kopien ihrer digitalen Werke auf Analogfilm herstellen, um deren Fortbestand zu garantieren und damit sicherzustellen, dass weiterhin Filmmaterial produziert werde: "Das ist nicht Romantik, nicht Nostalgie, das ist reine Gier", meint Kubelka. "Das ist wunderbar, denn Gier ist ein ganz starkes Motiv: Das hält!"

"Cinema Futures": Film Review, by Neil Young, Hollywood Reporter, 20.12.2016 (Article)

Versatile Austrian writer-director-editor Michael Palm ruminates on the problematic evolution of his chosen art form in Cinema Futures, a likeably wide-ranging documentary that will be catnip for celluloid-centric cinephiles. Marginally wider audiences may be attracted by the presence of Martin Scorsese, Christopher Nolan, Apichatpong Weerasethakul and Tacita Dean among the slew of talking-head contributors, although such luminaries´ contributions are tantalizingly brief, especially in light of the doc´s generous two-hour-plus running-time.

Having premiered in at Venice in September, the picture — commissioned to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Vienna´s Austrian Filmmuseum in 2014 — will play in January at Rotterdam, plausibly springboarding from the Dutch jamboree to North American festival and small-screen exposure.

"I feel like a stonemason justifying my use of marble," comments Nolan, who — like fellow 35mm-diehards Quentin Tarantino and Scorsese — misses very few opportunities to vocally defend the old-school, supposedly obsolete format. "Use it or lose it!," exhorts the Dark Knight auteur.

Palm meticulously traces the oft-discussed transition from analog to digital that has steadily — some would say stealthily — taken place in the 17 years since the release of Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace. This process has regularly generated fractious controversies — such as the current flap over the (spoiler alert!) CGI resurrection of Peter Cushing in Rogue One — and Palm, narrating in slightly dry German (he´s no Werner Herzog), guides his audience through most of them.

Cinema Futures functions best as a useful primer not only on the whole digital-vs-analog business (as previously addressed by the Keanu Reeves-produced 2012 documentary Side by Side), but also with regard to the role and importance of archives, and contentious matters of preservation and restoration. Scorsese, as always, provides maximum value in his intermittent appearances, beating his familiar drum that "movies need people to take care of them, and to keep taking care of them."

Palm clearly agrees, returning again and again to such shrines of restoration/preservation as the Vienna Filmmuseum (despite its name, this "museum" is in fact a rep cinematheque boasting a considerable archive) and two stateside counterparts: the Library of Congress near Washington — whose vaults, we learn in a typically offbeat aside, were previously used as the Federal Reserve´s gold stash — and George Eastman Museum in Rochester, N.Y.

At times during these sequences, the film veers uncomfortably close to the boosterish tone of a fund-raising project, and Palm is on more engaging ground when expounding on the grander philosophical contexts and implications of moving-image preservation. Each of the three principal locations provide intriguing vistas and no end of enthusiastic geekery from those employed therein ("We´re gonna be making film for many years," effuses a bigwig at Rochester´s Kodak), although a broader geographical/sociological spread wouldn´t have gone amiss.

In the second half of the doc, Palm does finally escape the West, though even at Mumbai´s Reliance Mediaworks — devoted to the painstaking business of restoration — his interviewees remain Anglophone. All the more welcome, then, that Jacques Ranciere and Nicole Brenez are also on hand. True to the French intellectual tradition that has long been associated with the more rarefied interpretations of the cinematic medium, they muse expansively on film´s role as "a vast reservoir of possible histories," and the importance of "conserving a part of the collective memory — the memory of humankind" while avoiding being trapped by "dominant historical discourse."

Palm, who periodically appears on camera with his crew, strikes a generally successful balance between various levels of analysis and approach, and bookends his speculations with a charming, anecdotal, illustrated memory of himself being captured on 8mm film as a small child.

But there´s ultimately a sense that Cinema Futures perhaps overreaches itself in its attempt to appeal to too wide a demographic. Palm´s own filmography has alternated unpredictably between the relatively accessible (2004´s Edgar G. Ulmer: The Man Off-Screen) and the more spikily experimental-esoteric (2011´s Low Definition Control: Malfunctions #0), with Cinema Futures occupying a slightly uncomfortable in-between zone: too basic for experts, too esoteric for newcomers. Then again, given cinema´s perpetually unresolved no-man´s-land locus between the glorious analog past and a hazardous, digital-dominated future, perhaps there´s something to be said for falling gracefully between stools.

(Neil Young, Hollywood Reporter, 20.12.2016)

Film Review: "Cinema Futures", by Jay Weissberg, VARIETY, 01.10.2016 (Article)

Without the narration, “Cinema Futures” could easily see significant TV sales, but given that Palm´s monotone delivery and deadpan philosophizing recall Mike Myers´Dieter character, it´s hard to imagine much play outside continental Europe, apart from scattered festivals. It´s a great pity, as the director brings together an impressive array of talking heads and draws attention to issues, such as preservation and custodial problems, that preoccupy the archival world but have yet to filter into the popular consciousness. Unlike Chris Kenneally´s “Side by Side,” which discussed similar matters, Palm´s documentary definitely takes sides and mourns the disappearance of celluloid, yet doesn´t do enough to bring out the aesthetic losses – which really are quantifiable – inherent in the wholesale ejection of analogue.

More Reviews

SXSW Film Review: "Ready Player One"

SXSW Film Review: "Unfriended: Dark Web"

Much is made of a photo from the late 1990s showing a group of industry people gleefully advertising the death of film stock in anticipation of the premiere of “Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace,” though it´s unlikely anyone in the picture had any idea of the scope of the revolution to come, when Yoda himself would become a mere digitized simulacrum after once being played by Frank Oz. Pity that Palm doesn´t mention Ari Folman´s criminally underrated “The Congress,” with its hard-hitting approach to this very subject.

Blame for the collateral damage of film´s demise is squarely leveled at Hollywood, symbolized by a nighttime aerial shot of L.A. designed to make the city appear like the Death Star, accompanied by John Williams-type music. Fortunately, film historian David Bordwell takes a subtler approach, discussing the disproportionate allocation of power to the distributors who call the shots. By now the train of events has become fairly well-known: the stranglehold of the multiplexes, together with the force-feeding of 3D, coerced theater owners into digitizing their cinemas to the point where now it´s difficult to find movie houses that can project acetate.

The decline of Kodak is addressed, and the very real concern that, despite the company´s reassurances, the continued manufacture of film stock may not be financially viable in the near future considering how few directors continue to shoot on celluloid. Even when they do, the movies still need to be transferred onto digital in order to get released. Perhaps the biggest value of “Cinema Futures” is that it makes viewers aware that digital files need to be migrated and updated every five years or they lose cohesion, whereas acetate can last over 500 years when stored in the right conditions. What still hasn´t sunk in for the general public is that, as hypothesized by conservation student Laura Alberque, the rate of digital deterioration combined with the lack of understanding that files need to be migrated means that we´ll have far fewer watchable home movies in 20 years than our grandparents had. Yet apart from a handful of Cassandras, no one appears to be screaming about this.

Because Palm wants to tackle all the issues inherent in the analogue-digital divide, he inevitably drops several important points, most notably that while some might like to think we have the ability to screen films as they once were, it´s not true. Even if nitrate were projected (as it is at George Eastman Museum´s annual Nitrate Picture Show), the projectors themselves have changed, and it´s impossible to fully reproduce carbon arc lighting. We can look with fond nostalgia at the shimmering dust particles caught in the bright light of the projector´s throw, but in truth we´ll never be able to replicate the filmgoing experience of the past, also because photochemical emulsions are unstable. That gives them their warmth and beauty, argue Tacita Dean and Christopher Nolan, but also makes it impossible, as pointed out by Eastman curator Paolo Cherchi Usai, to pretend that any print is exactly how it was meant to be.

On the plus side, the documentary champions the work of archivists and acknowledges the monumental challenges they face in terms of preservation. It would have been good to include a few words about the scandalous lack of funds accorded these institutions for the crucial work they do – anyone thinking Martin Scorsese´s World Film Foundation has either the money or the time to save every “worthwhile” movie is living in a fool´s paradise. Also not mentioned are the benighted policies of certain governments that force archives to destroy their nitrate once preservation prints are made, robbing future conservators with improved technology the chance to extract better material from the original sources. Surely that would have been more meaningful than hearing Palm opining that film is like a vampire in a coffin.

(Jay Weissberg, VARIETY, 01.10.2016)

"Cinema Futures": Symphonie der Farben und Bilder als Datensatz, von Sven von Reden, Der Standard, 27.04.2017 (Article)

Wien – Die digitale Revolution glich im Kino eher einem Putsch. Daran erinnert ein Foto, das am Beginn von Michael Palms essayistischem Dokumentarfilm Cinema Futures steht – ein Bild, das jedem Filmliebhaber Schauer über den Rücken jagt. Darauf werfen eine Gruppe Geschäftsmänner und eine Frau fröhlich Filmbehälter in eine Mülltonne mit der Aufschrift "OBSOLETE": "überflüssig". Das war um die Jahrtausendwende, wenige Monate nachdem mit George Lucas´ Star Wars: Episode I: Die dunkle Bedrohung erstmals ein Blockbuster (auch) als digitale Kopie in die Kinos kam.

Ungefähr eineinhalb Jahrzehnte hat es gedauert, bis sich das Verhältnis umgekehrt hat: Heute sind im Kino fast ausschließlich nur noch "files" zu sehen und nicht mehr "films", Dateien und keine Filmrollen. Die "Putschisten", die den analogen Film nach über hundert Jahren von seinem Thron stießen, waren die großen Filmverleiher, erklärt Filmwissenschafter David Bordwell in Cinema Futures. Sie hofften auf immense Kosteneinsparungen, da zukünftig keine teuren analogen Filmkopien mehr benötigt würden.

Michael Palm hat sich für seinen Film an die Orte und zu den Menschen begeben, die weiterhin die Fahne des analogen Films hochhalten, seien es Filmemacher, Filmarchivare oder Filmwissenschafter. Dabei gibt sich der Österreicher keinen Illusionen hin: Er selber bezeichnet Cinema Futures als Film über "die Zukunft der Vergangenheit". Wird analoger Film zumindest als Alternative für Filmemacher erhalten bleiben, ihre Visionen umzusetzen? Und welche Rolle wird analoger Film zukünftig noch bei der Archivierung der Filmgeschichte spielen?

Für analoges Filmmaterial als nicht zu ersetzendes künstlerisches Ausdruckmittel plädieren bei Palm prominente Filmemacher wie Christopher Nolan, Martin Scorsese und die Künstlerin Tacita Dean. Scorsese meint, es sei gerade die Unkontrollierbarkeit des filmchemischen Prozesses, die gewissermaßen zufällig immer wieder entstehende Schönheit, die die Liebe der Filmemacher zum analogen Film erklärt. Nolan will sich für seine Entscheidung, analog zu drehen, nicht rechtfertigen müssen: Ein Bildhauer müsse schließlich auch nicht begründen, warum er sich für Marmor entscheidet. Der Brite war neben Quentin Tarantino, J. J. Abrams und Steven Spielberg einer der Filmemacher, der daran beteiligt war, Kodak dazu zu überzeugen, die Produktion von 35-mm-Material nicht einzustellen. Ob diese Entscheidung tatsächlich langfristig sein wird, ist allerdings ungewiss.

Bewusstsein des Archivars

Besonders abhängig von dieser Entscheidung sind die Filmarchive. Hier ist das Bewusstsein für die Wichtigkeit der Erhaltung von Film auf seinem originalen Trägermedium am meisten ausgeprägt. Die Interviews mit Filmarchivaren und die Bilder aus der Filmabteilung der Library of Congress und ähnlicher Institutionen bilden das Herzstück von Cinema Futures. Dabei wird deutlich: Die Entmaterialisierung von Filmen in Datensätze aus Einsen und Nullen erleichtert nicht etwa die Überlieferung der Bildinformationen für die fernere Zukunft, sondern erschwert sie, macht sie unsicherer und teurer. Während 35-mm-Material ein Jahrhundert lang Standard der professionellen Filmherstellung war, wechseln die digitalen Dateiformate ständig, ebenso wie die Ansprüche an die Auflösung der Bilder. Digitale Dateien müssen alle fünf Jahre umkopiert werden, während ein korrekt gelagerter Analogfilm nach Schätzungen über 500 Jahre hält. Weshalb etwa die Archivare von Sony dazu übergegangen sind, ihre digital produzierten Filme für die Lagerung auf analoges Material umzukopieren.

Trotz der zwei Stunden Spielzeit von Cinema Futures können viele Fragen nur angeschnitten werden. Eine kurze Sequenz, die in Indien spielt, bricht den westlich zentrierten Blick etwas auf. Doch was ist zum Beispiel mit der Rettung des Filmerbes in Afrika? Wie gehen Filmgroßmächte wie Japan oder Russland mit ihrem analogen Erbe um?

Auch das Thema digitaler Restauration wirft grundlegende Fragen auf, die hier nur am Rande vorkommen. Statt an diesen praktischen Fragen dranzubleiben, geht Palm immer wieder auf eine höhere, abstrakte Ebene, indem er als Off-Kommentator über den Status des Filmbildes philosophiert. Diese Kombination aus weitgefasstem Thema und vielfältigem Ansatz ist ambitioniert, läuft aber immer wieder Gefahr, beliebig zu wirken. Dennoch bietet Cinema Futures einen guten Überblick über ein Thema, das jeden angeht, der sich schon einmal gefragt hat, was mit seinen Handyfotos in 50 Jahren sein wird.

(Sven von Reden, Der Standard, 27.04.2017)

Cinema Futures

2016

Austria

126 min

Documentary

English, German

English, German, french, italian